Makgeolli Secrets: Understanding Nuruk, the Wild Starter Behind Korean Rice Wines

More about pear-blossom liquor, a mysterious wild starter, and the brewing process behind this fruity, creamy rice wine.

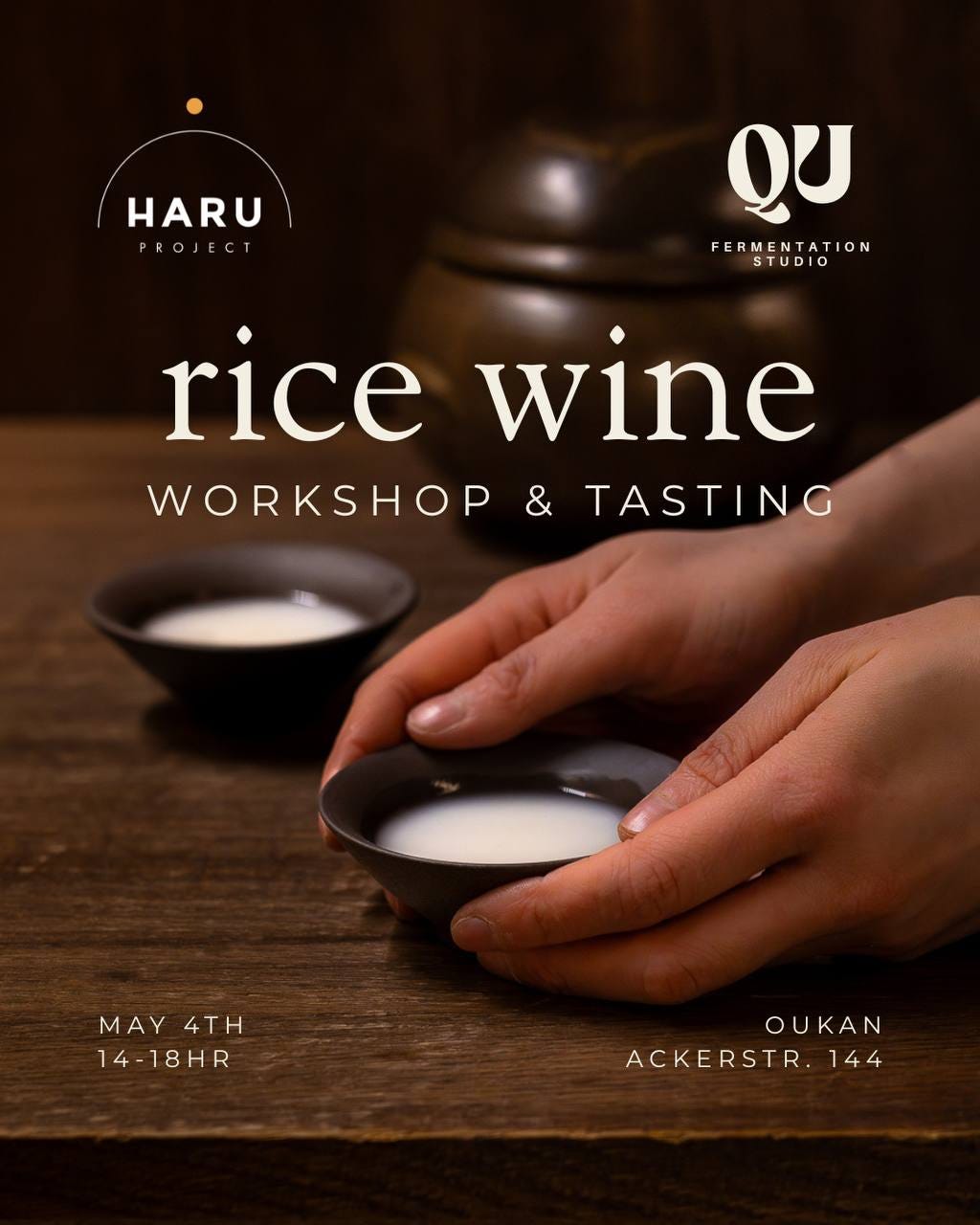

Last week we announced our HARU PROJECT x QU Rice Wine Workshop where we’ll be brewing makgeolli together to take home and tasting various sorts of makgeolli and soju paired with a few banchan plates. If you haven’t signed up already, make sure to do it here.

We will now dig deeper into the past and present of how makgeolli is produced.

Makgeolli has a rich history spanning over 2,000 years in Korea. Its origins trace back to the Three Kingdoms period (57 BCE–668 CE), with the earliest documented mention found in the Goryeo Dynasty's Jewangun-gi (The Poetic Records of Emperors and Kings), where it was referred to as ihwa-ju (“pear blossom” alcohol)—more on that later. Traditionally, makgeolli was a rustic farmer’s homebrew using rice, water, and nuruk—a fermentation starter containing wild yeasts and bacteria. Its low alcohol content and supposed nutritional benefits made it a staple among the working class, and it still maintains a reputation of being highly accessible to drink and something that older generations might brew at home. During the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1897), makgeolli was often brewed at home for the purpose of casual drinking as well as for usage in ancestral rites. Throughout the 1900’s the Korean government passed several laws in order to bolster grain farming and alcohol industries by restricting homebrewing practices, so by the late 20th century, makgeolli brewing had largely fallen out of favor and commercial makgeolli became overshadowed by Western alcoholic beverages. In recent years however, makgeolli and traditional Korean alcohol (known collectively as “sool”) has seen a resurgence driven by younger generations seeking out artisanal products. Modern brewers have revitalized makgeolli by experimenting with flavors and packaging, making it more appealing to contemporary tastes.

Understanding Nuruk and Koji’s Place in Makgeolli Brewing

In mainstream Korean makgeolli brewing, the use of nuruk has been largely exchanged for the use of koji, the same mold-based rice starter used to make sake and other Japanese products like shoyu and miso. What is nuruk exactly, and why is its use less common today in commercial brewing?

While I’m a far cry from being an expert at even homebrewing, my brief stint learning from Korean American brewery Hana Makgeolli taught me a few things about nuruk, a cake of pressed crushed grains like wheat, barley, or rice left to sit in “nuruk rooms” filled with rice straw to encourage the growth of a wide variety of bacteria, yeasts, and molds on the cake. Nuruk cakes are made both in the summer and winter, with only a few small producers left in Korea doing this at a small commercial scale. Much like qu, nuruk is a wild starter whose microbiological makeup is as consistent as you might expect when you leave something sitting out in a room to establish its own microbiome in varying seasons—which is to say, not at all.

That is not to say there isn’t any element of human intervention involved in the production of nuruk. Nuruk houses are often made of wood, concrete or other porous materials which are microbially permeable, and the result of growing batch after batch of nuruk in the same space ultimately reinforces colonies of wild microbes in the air and housing structure itself. The practice of filling the nuruk rooms with rice straw encourages the growth of specific molds like Aspergillus oryzae, the same mold strain used in koji production. Nevertheless, using wild-fermented nuruk in brewing at a commercial level is extremely challenging due to its variable microbial makeup, and this is where the experience of a master brewer comes into play. Using nuruk in a brewing formula means adapting to each batch as it brews, and controlling other variables like time, temperature, and when to feed the batch a new addition of rice. Learning the ins and outs of your brew process is already difficult enough in sake brewing, which typically uses a single designer strain of koji throughout the entire process. While nuruk can create delicious and complex brews, it also can cause brews to go awry, causing strong off-flavors or bitterness depending on the starter batch itself and brewing conditions. Using designer koji strains that have specific enzymatic profiles offers makgeolli brewers control and consistency of product, a critical factor when stakeholders are waiting on returns and customers expect each bottle to taste the same as the last.

Sharing our Experiments and Understanding Styles of Makgeolli

In our workshop on May 4th, we’ll be making a two-stage brew in our workshop for you to take home, meaning that after the initial stage of mixing water, koji, yeast, and steamed rice together we’ll feed the batch again with more koji and steamed rice for a deeper, more complex flavor. In addition, we’ll have some experiments made with various combinations of koji, brewing yeasts, and nuruk to try.

HARU PROJECT will also be bringing some samples of Cheongju and Ihwaju to taste. During our exchanges, I was particularly struck by the method and taste of Ihwaju, or “pear-blossom” alcohol. Thick and fragrant, Ihwaju differs from other kinds of rice wine in that is a thick rice paste eaten with a spoon. The sample Eunji and Sanghyun from HARU PROJECT gave me was rich with fruity pineapple notes, sweet and pleasantly yogurty in flavor. Only mildly alcoholic, it reminded me of a more pineapple-y and lactic version of amazake, something I’d crave to eat if I haven’t been eating well lately. Below is a little peek of how Ihwaju is made, but I’ll leave the real explanation to our experts during the workshop.

Join our Workshop

I hope many of you can join us. Even if you’re not interested in brewing at home by yourself this is a rare chance to try a wide variety of home-brewed makgeollis that you won’t be able to find commercially available, and the team at HARU PROJECT has really put a lot of work into making the traditions and a huge range of makgeolli available to participants. I’ll be making some traditional banchan dishes to pair with our makgeolli and soju tasting, and also assisting in the brewing process. Register here.

Thanks for reading.

Polly